The Great Thirst

In Ireland they don’t call it the famine – those years in the mid-19th century when English landlords exported huge quantities of grain and beef while a million Irish people were dying of starvation and a million more were leaving their homeland. They call it “the great hunger” because the blackened blight of the potato, the lone food on which peasant lives depended, caused massive suffering in the midst of agricultural plenty. It wasn’t a famine. It was a policy. So we read now of California, whose farmers produce most of America's fresh food, consume four-fifths of the state’s vanishing water, and are exempt from Gov. Jerry Brown’s mandatory water restrictions. California, where almonds, the most lucrative export, use 1.1 trillion gallons a year, where it takes 872 gallons of water to make a gallon of wine, 1,847 gallons for a pound of beef, and 4.9 gallons for a single walnut.

The drought is real in California, its end is nowhere in sight. And while farmers didn’t stop the rain, longstanding agricultural policies and practices exacerbated the long-predicted crisis.

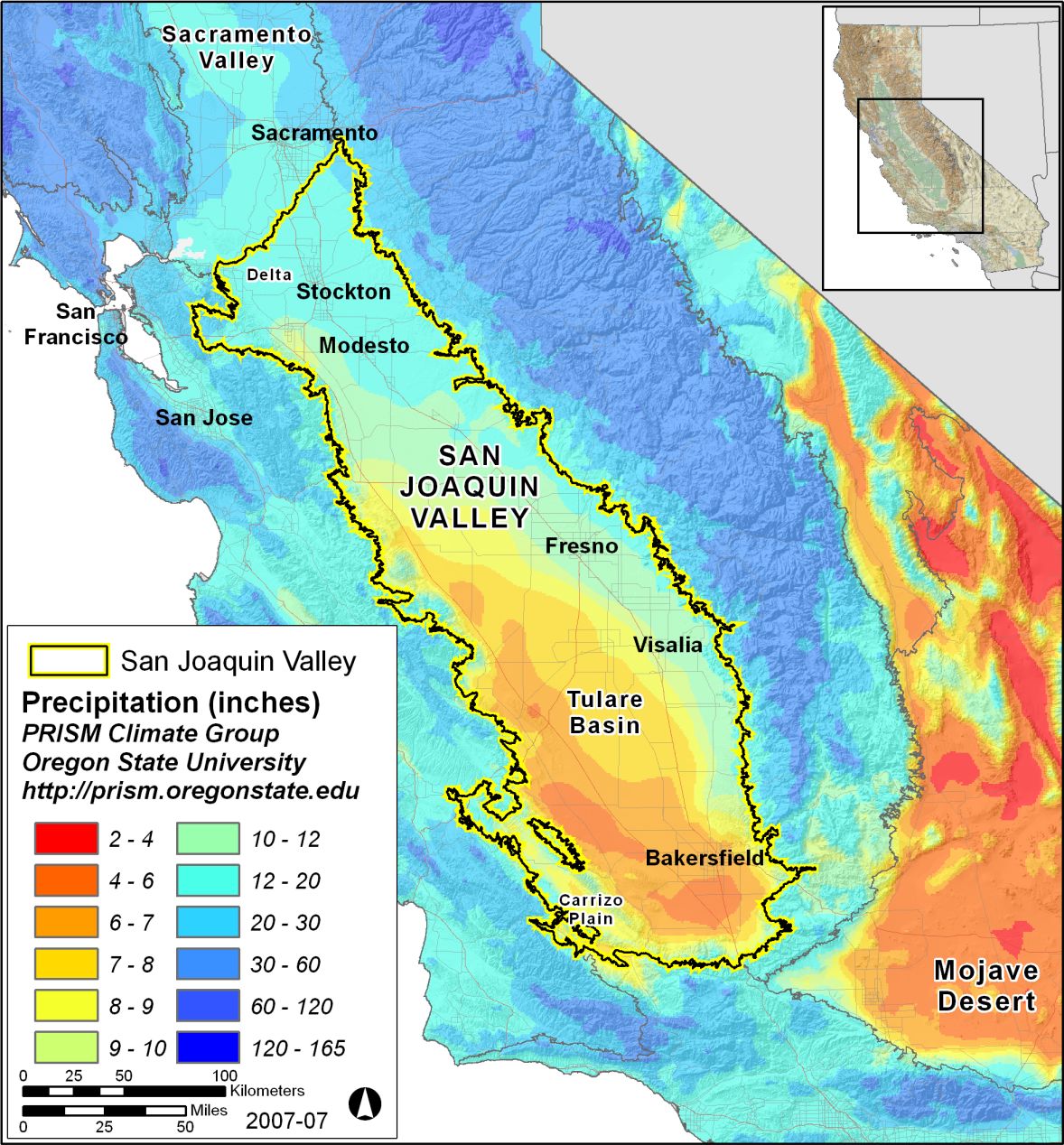

The San Joaquin Valley didn’t become “the nation’s salad bowl” on its 15 inches of annual rain. It took massive irrigation projects and the diverted waters of the Colorado River to make the southwestern desert bloom. And it is one more testament to what Marc Reisner, in Cadillac Desert, deemed “the West’s cardinal law: that water flows toward power and money.”